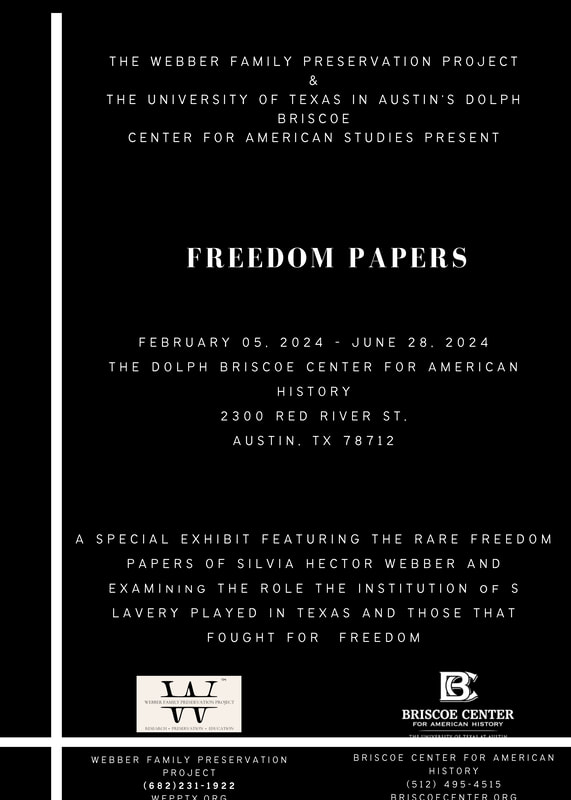

The Webber Family Preservation Project is proud to announce the exhibit “Freedom Papers”

This exhibit will run open in February for Black History Month through June and features the unique and rare freedom papers of Silvia Hector-Webber. Below are some documents that aid in the contextual understanding of Silvia’s papers, their meaning in Texas during the pre-Republic era, and what freedom looked like in independent Republic, Civil War, and reconstruction era Texas and the United States.

.

transcription of the Freedom paper documents

Contextual Background

and

Biographical Information

The below document is a Travis County deed that showcases the land forfeiture of Silvia and John Webber of their vast Webberville holdings, located just outside of present-day Travis County. This is one of the documents that evidences how the Webbers chose to give up valuable land before ever considering paying John Cryer what he asked in exchange for the freedoms of Silvia and her three children.

Silvia's Texas enslaver did not want money or specie, in exchange for Silvia and her children's freedoms. He wanted a much higher price. This enslaver requested that John and Silvia, before the final day of October of that year (1834) deliver to him two enslaved children, specifically one enslaved boy who was no older than 2 years of age and one enslaved girl who he required to be no older than 3 years of age.

While Silvia's freedom papers reveal the high price John Cryer asked in exchange for her freedom, neither Silvia nor John ever paid such a hefty price. October of 1834 arrived as fleetingly as it passed, and Cryer did not receive payment.

This deed record exposes that the Webbers refused and avoided making payment to Cryer for over 15 years. By July of 1850, however, they were pressured to pay up, principally because Cryer was bankrupt and needed money fast. At that point, the Webbers chose to forfeit all their property at Webberville in order to settle the debt they owed Cryer

Silvia's Texas enslaver did not want money or specie, in exchange for Silvia and her children's freedoms. He wanted a much higher price. This enslaver requested that John and Silvia, before the final day of October of that year (1834) deliver to him two enslaved children, specifically one enslaved boy who was no older than 2 years of age and one enslaved girl who he required to be no older than 3 years of age.

While Silvia's freedom papers reveal the high price John Cryer asked in exchange for her freedom, neither Silvia nor John ever paid such a hefty price. October of 1834 arrived as fleetingly as it passed, and Cryer did not receive payment.

This deed record exposes that the Webbers refused and avoided making payment to Cryer for over 15 years. By July of 1850, however, they were pressured to pay up, principally because Cryer was bankrupt and needed money fast. At that point, the Webbers chose to forfeit all their property at Webberville in order to settle the debt they owed Cryer

By the time Webber had repaid Cryer in land, Cryer was financially destitute as is evidenced by the margin notes in the Travis county deeds pictured above that show Cryer signed over the land that same day to J.B. Banks.

Newspaper announcements about the acquisition of the land by Banks show the land had increased from $1-$2 per acre when Webber first settled it, to $15 an acre by 1850. This shows that along with the $900 in compounded interest that the human life asked for by Cryer was never repaid. This can be viewed as an early act of resistance against the institution of slavery, the first of many for the family.

Distinction between other Emancipation and manumission papers

Another unique aspect of these documents is the structure in its distinctive and clear terminology, John Webber did not purchase Silvia or their 3 children in order to free them. As the narrative above explains these serve as true “Freedom Papers” and are structured in an almost unprecedented fashion. Not only is the fact that John Webber is not purchasing Silvia or their children unique, but also the fact John Webber was not their enslaver to begin with, nor did he own them even for a moment in order to arrange their freedom.

The vast majority of manumission, emancipation, and bonds where enslaved people are freed have been drafted by the enslaver. In most cases involving women and children the enslaver is the father of the children conceived in a nonconsensual relationship with the mother of the children who were born enslaved due to the status of the mother. This is another area where the freedom papers differs significantly from almost all other examples available.

A clear example of that is the case of Mary Martin and the freedom of her enslaved slaved children in West Felicia Parish Louisiana. Their freedom was granted by Thomas Purnell who was not only their enslaver but also the father of Mary’s children. While he did free his own enslaved children and their mother he also showed no concern for the children of other enslaved women as he continued to both utilize slave labor and engaged in the purchase of other enslaved men, women, and children contributing to the destruction of enslaved families. While Purnell did acknowledge his children and ensure their freedom, his actions in enslaving others leaves little doubt he was fully supportive of the institution of slavery. *

Distinction between other Emancipation and manumission papers

Another unique aspect of these documents is the structure in its distinctive and clear terminology, John Webber did not purchase Silvia or their 3 children in order to free them. As the narrative above explains these serve as true “Freedom Papers” and are structured in an almost unprecedented fashion. Not only is the fact that John Webber is not purchasing Silvia or their children unique, but also the fact John Webber was not their enslaver to begin with, nor did he own them even for a moment in order to arrange their freedom.

The vast majority of manumission, emancipation, and bonds where enslaved people are freed have been drafted by the enslaver. In most cases involving women and children the enslaver is the father of the children conceived in a nonconsensual relationship with the mother of the children who were born enslaved due to the status of the mother. This is another area where the freedom papers differs significantly from almost all other examples available.

A clear example of that is the case of Mary Martin and the freedom of her enslaved slaved children in West Felicia Parish Louisiana. Their freedom was granted by Thomas Purnell who was not only their enslaver but also the father of Mary’s children. While he did free his own enslaved children and their mother he also showed no concern for the children of other enslaved women as he continued to both utilize slave labor and engaged in the purchase of other enslaved men, women, and children contributing to the destruction of enslaved families. While Purnell did acknowledge his children and ensure their freedom, his actions in enslaving others leaves little doubt he was fully supportive of the institution of slavery. *

Thomas Purnell Petition to free Mary and her children. From the personal archive of Dr. María Esther Hammack

Unlike the cases of Thomas Purnell and the Josias Gray family included in the Briscoe physical exhibit, John F. Webber never owned Silvia, or their children, or any other enslaved persons. This is an important aspect of Silvia's story and of her children's experiences. This fact offers insight and inquiry into Silvia's intellectual contributions and actions, perhaps the negotiations that she endeavored to be free. It allows us to explore her story in ways that make us cognizant that her experience was not merely one in which a white man bought her or one in which a white man could, would, or should receive all the credit for her own fight and role in her own liberation (and the liberation of her children for that matter). John Webber never owned her because he never bought her. The language in Silvia's freedom papers make that clear. John bought her freedom and undoubtedly did so through a plan of her own pursuit and doing.

The role of power dynamics and relationships in enslavement and in freedom

These documents also give much-needed nuance and insight to the complexities faced in our collective history. While the fact that Silvia was enslaved by another man not John Webber is important, the fact that she was enslaved makes us confront the reality and definition of consent. This cannot not be overlooked or minimized. And certainly should never be romanticized. These freedom papers show clearly that Silvia was enslaved during the birth of her first three children and did not have the right or the ability to either give or deny consent. For this reason is important to note that ascribing “love” or “romanticizing” this relationship would be inappropriate and inaccurate by definition. The violence Silvia endured while enslaved deserves recognition, not minimization. It also relevant to overemphasize that their relationship was incredibly complex and today much of their story, before 1834, remains riddled with many silences. At the cost of distracting from their actions in aiding Freedom Fighters to self-liberation, our goal is to make visible the clear impact and importance Silvia had on John Webber, on his life, and his future, as evidenced by their long shared life and the world their descendants ---Black, Brown, and Mixed-- made.

While a documented legal marriage hasn’t been found, it should be noted that these papers also make us look closer at the laws and mentality surrounding enslaved persons and Anglo settlers during the Mexican Texas period and the imbalance of power dynamics. The historical archive has many a report by through various sources that reveal and attest to the fact that Silvia and John were married by Father Michael Muldoon. Muldoon was the priest assigned to Austin’s colony in Mexican Texas, sent there from the diocese of Linares, Nuevo León. While we do not have Muldoon’s parrochial records as they went back to Mexico after Texas declared independence and became a republic, we do have proof of him performing both baptism and marriage services for Black persons living in Texas.

The document below is from an announcement that Father Michael Muldoon had printed in both Spanish and English in a newspaper. This newspaper was disseminated to all the residents of Mexican Texas & Coahuila y Texas on May 26, 1831. In it he said he would

“baptize and marry both sexes of the black race without receiving from them or their masters any gratification”

In addition to Muldoon’s announcement, the laws of Mexico-Texas allowed for interracial marriage due to the Mexican government having abolished slavery in 1829. There are examples in Texas legal history, where recognition of the marriages that took place before the Texas Republic reinstated slavery and legally forbid interracial marriage were considered legally binding as they took place before Texas became a Republic and passed the law making interracial marriage illegal.2

The nature of John & Silvia’s relationship after her freedom is clear in that they lived as man and wife and raised their family together and remained together till their deaths. Their legal marital status after her freedom is not known, but the option and freedom for them to have been married did exist. We know that Silvia collected a widows pension from John Webber’s war of 1812 service after his death.

While we cannot speculate on how their relationship began or if it was a relationship based on mutual affection, we can determine from John’s actions that Silvia was a significant influence and partner to him as evidenced by the heavy price he paid in his forfeiture of land holdings, moving to the Rio Grande Valley and his actions in the fight against slavery and his eventual arrest by the Confederate army by General John Salmon “Rip” Ford for his role as a Union Sympathizer. Her value and impact are undeniable in the context of the legal system in place at that time, the negotiations of her freedom and her three children, and the actions of John Webber to both protect his own family by moving out of the settlement he built with Silvia to the Rio Grande and risking life and limb at the hands of the Texas Rangers who served as “slave patrol” and “slave hunters” on the Texas Mexico Borderlands where they aided others to Freedom in Mexico via their licensed ferry.

The nature of John & Silvia’s relationship after her freedom is clear in that they lived as man and wife and raised their family together and remained together till their deaths. Their legal marital status after her freedom is not known, but the option and freedom for them to have been married did exist. We know that Silvia collected a widows pension from John Webber’s war of 1812 service after his death.

While we cannot speculate on how their relationship began or if it was a relationship based on mutual affection, we can determine from John’s actions that Silvia was a significant influence and partner to him as evidenced by the heavy price he paid in his forfeiture of land holdings, moving to the Rio Grande Valley and his actions in the fight against slavery and his eventual arrest by the Confederate army by General John Salmon “Rip” Ford for his role as a Union Sympathizer. Her value and impact are undeniable in the context of the legal system in place at that time, the negotiations of her freedom and her three children, and the actions of John Webber to both protect his own family by moving out of the settlement he built with Silvia to the Rio Grande and risking life and limb at the hands of the Texas Rangers who served as “slave patrol” and “slave hunters” on the Texas Mexico Borderlands where they aided others to Freedom in Mexico via their licensed ferry.

John Webber’s War of 1812 Pension Index card showcasing Silvia as his widow. From the personal archive of Leslie Trevino.

John Webber’s War of 1812 Pension Index card showcasing Silvia as his widow. From the personal archive of Leslie Trevino.

Whether or not documentation exists of their marriage, had The arrangement of Silvia and their three children’s freedom not been made at the time that it was and in the way that it was, the lives of Silvia and her children would have. looked very different. Because of the freedom we find described in the freedom papers all but three of Silvia‘s children were born free as the status of the child followed out of the mother, and they never knew the horrors of slavery. These papers also give us the first look at Freedom for Silvia, the price that it cost, the intelligence and powerful influence of a Black Woman who went on to aid others to freedom, despite the risk that it posed to her own and her children’s tenuous at best, fragile freedom. In her decisive, intentional, and still visible actions these papers show autonomy and strength and help bring Silvia out of the relegated position of the “formerly enslaved Black wife” of an altruistic and magnanimous Anglo Texas settler and situate her front and center in the fight for freedom in Texas and serve as testimony to her struggle and triumphs.

These papers serve as a timely and prescient glimpse into the complex and nuanced realities of history that we have left unconfronted and still remain unresolved. It is the sincere hope that our children and their future generations will benefit from their contents and continue to educate the state, our country, and the world about the history and voices that have been made silent until now and bring Silvia the recognition and due respect she has been long overdue and denied.

These papers serve as a timely and prescient glimpse into the complex and nuanced realities of history that we have left unconfronted and still remain unresolved. It is the sincere hope that our children and their future generations will benefit from their contents and continue to educate the state, our country, and the world about the history and voices that have been made silent until now and bring Silvia the recognition and due respect she has been long overdue and denied.